A Brief History of Sport for Life

He wondered if they could turn their ideas into pictures.

In the early 1990s, while Richard Way was working as a coordinator of coach education for the B.C. government, he encountered the visionary work of Istvan Balyi, a defected Hungarian sport pioneer. Balyi had been brought to the west coast by Bob Bearpark of the B.C.’s government’s sport branch to work with Team B.C. and the National Coaching Institute. At the time he was the only sport scientist in the country considering planning and periodization in relation to athlete training, and his work was beginning to gain traction internationally. As Way attempted to wrap his head around the ideas being advanced by his colleague, he tried to envision how these concepts could be implemented into national sport organization (NSO) programming to benefit athletes. He kept finding himself translating Balyi’s complex papers into visual models and graphics.

Istvan Balyi

“I was coaching at the national level at that point, and he would introduce these complex ideas, so I would draw pictures and graphics and say ‘is this what you mean?’” said Way, nearly 30 years after he began work with Balyi, which resulted in the creation of the Long-Term Athlete Development framework and a new normal for the Canadian sport system.

“It was a two-way street where he was the brilliant physiologist that looked at planning and periodization, and I was the pragmatic systems guy who was looking at the athlete and what you really needed to effectively implement their planning. We complemented each other’s skills, with his intellect and academic perspective juxtaposed against my practical ‘how can I create a system around my athletes to utilize this knowledge’ focus.”

He couldn’t have known it at the time, but his partnership with Balyi was the first step in a multi-decade journey that would impact the sport and physical activity landscapes of Canada and beyond. Their work would lead to the birth of Sport for Life, a flourishing non-profit with a $5-million-per-year budget composed of professionals dedicated to the promotion of physical literacy and quality sport. Twenty-five years ago he never would’ve dared dream that big.

Putting together the team

When Balyi and Way first teamed up, they were focused primarily on quadrennial planning that revolved around the Olympics and Paralympics. As an international-level-luge-athlete-turned-coach, this made sense to Way. But as Balyi continued his work with an increasing number of sports, he began to create a universal framework destined to radically transform the status quo. With a more holistic approach in mind, this framework sought to follow the athlete right from their first experience to their post-competitive life. The first framework of this sort, the Athlete Integration Model, Balyi completed for Alpine Canada in the late-’90s.

“Istvan was a pioneer, a thought leader, a catalyst for change. When he worked with a sport, the coaches always came away with so much more understanding of how to prepare athletes for success in the short- and long-term,” Way said.

Alpine Canada

Then Ireland came calling. In early 2000 the Irish Coach and Athlete Training Institute reached out to Balyi to see if he could influence change within their system. That work resulted in the Irish Pathways in Sport framework. Sport England was not far behind as their national sport governing bodies rushed to modernize their systems leading up the 2012 Olympic Summer Games in London. The timing was perfect. Balyi’s work was now being internationally recognized as a revolutionary approach to sport, while at the same time Sport Canada was leading the creation of Canada’s first ever Sport Policy. The creation of the Sport Policy, combined with Canada winning the rights to host the 2010 Olympics, were the catalysts to the creation of two significant initiatives: Own the Podium and Long-Term Athlete Development, which would eventually be renamed Long-Term Development in Sport and Physical Activity.

Once Sport Canada expressed interest in Balyi’s innovations, he and Way enlisted three new experts to put together a team of five that included Charles Cardinal, Dr. Colin Higgs and Dr. Steve Norris. Soon after Dr. Mary Bluechardt and Dr. Vicki Harber would be added to the leadership group. They started in 2004 working on seven sports at a time, racing to create a framework for all 56 NSOs in Canada. Included in that first wave of sports were volleyball, basketball and rowing. Each one went through an 18-month to two-year process with exciting results.

An overview guide called Canadian Sport for Life–Long-Term Athlete Development was completed in 2005 and approved by the federal government as the Long-Term Athlete Development framework for Canada. Two years later all the provinces signed on too. It took until 2009 to have all federally funded NSOs complete their sport-specific framework, at which point the foundation for a modernization of Canadian sport was complete.

What’s in a name?

It was time for Way to put his money where his mouth was. Back in 2003 the B.C. government downsized the sport branch, and he was given a choice: apply for one of the remaining positions or move on to new things. With three children under the age of five and his wife employed part-time, he felt like he couldn’t leave, but it was time to go regardless.

Lean years ensued as he worked diligently to advance Balyi’s ideas so the pair of them could eke out a living, funded by contracts from Sport Canada. They were awarded $25,000 to write Canadian Sport for Life–Long-Term Athlete Development, then given $350,000 a year to collaborate with NSOs on implementation, contract subject matter experts to put their theories into practice, and host events. Working next to the furnace in his home, he hired an assistant named Danielle Bell in 2005, a record-setting varsity swimmer who graduated from the University of Victoria with a degree in psychology. She would work alongside him for the next eight years.

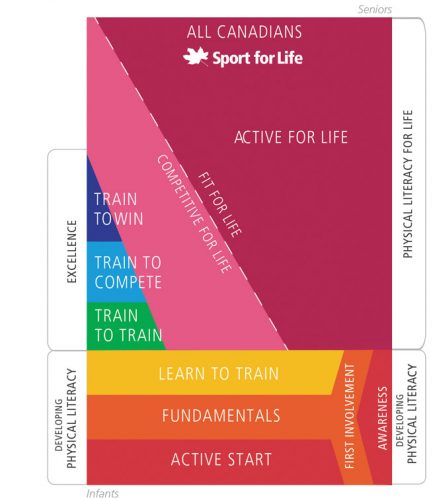

The Sport for Life Long-Term Development rectangle

By this point, the ballooning leadership group of sport experts working with Balyi and Way were being embraced by sport organizations and stakeholders alike, so they realized they would need a moniker for their burgeoning movement. It was during a routine meeting in 2005 that Higgs suggested “Canadian Sport for Life”, which caught on immediately. There was little discussion; everyone loved it.

“As time went on, people were referring to Canadian Sport for Life more and more, and looking at the work we were doing. It was becoming a movement based on modernizing sport looking at the whole life of an athlete along with the systems that support them as opposed to the repetitive cycles of quadrennial planning. A few were opposed, but most embraced us with open arms. They saw the logic in moving from the exclusionary ‘pyramid’ to the inclusive ‘rectangle’,” said Way.

“And even some of those who were opposed were mimicking what we were doing under a different name. Now in a sense it didn’t really matter, because we were all about being catalysts for change. You can be a catalyst in a few different ways, whether you’re getting credit for it or if someone’s doing it in response to what you’re doing. We were just happy to see Canadian sport progress.”

As the movement grew, more talented people contributed such as Carolyn Trono, Dr. Paul Jurbala, André Lachance, and Christian Hrab — the latter two contributing to the francophone capacity of the organization. Wanting to have more of an inclusive and international profile, it was later decided by the leadership group to drop the first word of the movement’s name and become Sport for Life.

Becoming a non-profit society

As 2010 approached, it was clear that the leadership group’s vision would carry the movement even farther into the future than they had planned. Now that all of the NSOs had developed their own sport-specific models of the Long-Term Athlete Development framework, they had to figure out how to implement it. And that would take time and guidance. Critical to achieving that goal over the years were champions within the government, especially Sport Canada, where Dan Smith, Phil Schlote, the late Carol Malcolm-O’Grady, Lane McAdam and Francis Drouin and others could see how Long-Term Athlete Development had the potential to be the catalyst for many kinds of success.

Key to sport organizations across the country rallying around Long-Term Athlete Development was the creation of an annual opportunity for everyone to come together. Starting in 2006, Canadian Sport for Life began hosting its Summit in Gatineau. Though there were only 60 people at the first one, by the fourth year that number more than quadrupled to 240.

“One of our core strategies was to get everyone together to celebrate and share. We had a sprinkle of international presenters with a main focus of Canadians doing great work,” said Way.

“When I reflect and think we eventually hosted these events with 500 delegates, with only a few of us and Danielle doing everything, it was amazing. It was a really big deal when we hired a second full-time staff member, Thom Brennan, while I was working on contracts for the B.C. government around 2010. He was incredibly sharp, and was the first to realize that if we were going to achieve our dreams we would need to find more funding sources. He really gave us a boost.”

The Sport for Life team

Canadian Sport for Life had benefited from 12 years without overhead costs; they hadn’t paid for rent, insurance, administration or any of the other typical bills associated with running this sort of enterprise. Their initial Sport Canada funding through the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific (CSI-P) had ballooned to $500,000, while they’d matched that with $500,000 of funding through Way’s consulting business Citius. By operating out of Way’s home they’d been able to funnel extra funds towards developing materials and expanding their annual Summit—but by 2014, it was time for a change.

“We’d always been working internationally all along, but with a focus on Canada. We had developed capacity in both official languages. What was becoming more and more evident post-2010, which was a huge year for Canadian sport, was that we were going to be around long-term. We had been expanding our work with different projects since 2010, but if we were going to really grow then we needed to look at becoming a non-profit society,” Way said.

“Then Sport Canada said ‘look, it doesn’t seem like you’re going away and we see a continuing role for you, continued activation work with national sport organizations, and we don’t want you to work through the National Sport Centre anymore’.”

Once the movement had incorporated into a federal non-profit called Sport for Life, the decision was made to funnel all that funding through Sport for Life. During this time of rapid change Wendy Pattendan came on to mentor the transition from movement to organization, initially as CSI-P program oversight and then as the first chair of the Sport for Life Board of Directors. The transition culminated with the board initiation in October 2014, when Pattendan was joined by Dr. Mary Bluechardt, Roger Smolnicky and John Ross. Ram Nayyar followed soon after.

What is physical literacy?

Through work with Sport England in the early 2000s, Canadian Sport for Life’s leadership group had become aware of the term “physical literacy”, a concept invented in the 19th century and popularized by a British philosopher named Dr. Margaret Whitehead. The leadership group collectively decided to adopt the term, and then mobilize it. Physical literacy was destined to become the backbone of all the work they did, whether it was in the sport sector or not. It was seen as a chance to promote an active start to participating in sport for life.

Sport for Life CEO Richard Way

“We started with the idea of developing physical literacy to improve the fundamental movement skills of top athletes coming into national teams, many who had poor skill-performance habits they picked up earlier in their lives. It was a trigger to look at development in the long-term,” said Way.

“However, we quickly realized there were two additional strategies that were equally or even more important: increasing the value placed on physical education and physical activity in school settings as well as increasing the understanding that developing physical literacy is a community responsibility. It takes a village.”

The leadership group quickly found that their interpretation of the term was controversial, and not quite in line with Whitehead’s vision. While she was philosophical, Canadian Sport for Life took a more pragmatic approach that was relevant to its mandate. That resulted in the creation of Developing Physical Literacy: A Guide for Parents of Children Ages 0-12, a resource they published in 2006. Dr. Colin Higgs was the lead author, with other contributors such as Drs. Jurbala and Harber. Dr. Dean Kreillaars and Drew Mitchell then took the concept to another level. That popularization also brought academic researchers such as Drs. John Cairney and Dean Dudley to evaluate and eventually validate the impact of physical literacy.

“Whenever you create change, you’re always criticized for not keeping things where they were. There were people aware of the term in Canada, but they hadn’t seen the utility of popularizing it. Meanwhile we were off and running,” said Way.

“We were also pioneers with our Quebec partners to make sure the concept would be translated, adapted and accepted in French.”

Using the approach of gathering champions, Canadian Sport for Life began hosting a biennial International Physical Literacy Conference (IPLC) beginning in Banff in 2013. The event was then held in Canadian cities including Vancouver, Toronto, and Winnipeg, and then expanded outside of Canada in 2018 and 2019, being hosted in Manama, Bahrain and Umea, Sweden, respectively. With an aim of engaging beyond the sport sector, the conference regularly attracted hundreds of delegates from fields such as health, recreation and education.

Two different worlds

Once the Summit and IPLC conferences were well on their way, Sport for Life found itself connecting in two different worlds: sport and physical literacy. But according to Way, those two strands are way more interlinked than the average person realizes. As far as he’s concerned, the two streams are just two aspects of the same mandate: to give everybody the opportunity to become active and fit for life.

“The best expressions of physical literacy are high performance athletes, and I would include professional dancers in that. But to become a good athlete it comes back to physical literacy, and the motivation and confidence to express technically correct movement as part of Long-Term Development,” Way said.

PL4C in action

One of the projects that began shortly after the 2010 Winter Olympics was Community Connections, in which Canadian Sport for Life mobilized their physical literacy knowledge outside the sport system. Bringing together the health, recreation and education sectors, Way and his team worked with educators, practitioners and programmers to promote active living initiatives and encourage a culture of healthy living.

“Philosophically we’d always seen the connection between communities and physical literacy development, even in our earliest resources we talked about the value in connecting all these different sectors. But this is when we moved from it being a philosophy to actually running projects,” said Way.

Led by Lea Wiens and under the guidance of Ian Bird, the McConnell Family Foundation funded Canadian Sport for Life to engage nine Canadian communities. The learning curve was steep on how their expertise could be shared most effectively, by meeting communities where they were at and customizing an approach to quality sport and physical literacy development at the local level that suited each specific community. This led into a two-year engagement with the RBC Learn to Play project, which along with Community Connections evolved into the Physical Literacy for Communities (PL4C) initiative. Led by Sport for Life director Drew Mitchell, PL4C has reached over 25 communities in B.C. so far, as well as six in Ontario and two in Nunavut — and it continues to grow. The RBC Learn to Play project also helped in creating a durable partnership with Réseau Accès Participation that would give S4L more capacity to reach francophones in Quebec and all across Canada.

“Change was occurring all the time, and it is stressful, but organizationally you have to be courageous and take risks. You have to have energy for change, and passion. It’s a lot simpler to stay as you are, but you have to share and engage people into that change because if you change and nobody else changes it’s no good,” said Way.

“It’s like Einstein said: the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again while expecting different results.”

Creating an Indigenous pathway

As Sport for Life continued to broaden the scope of the work they were doing, Way teamed up with Canada Snowboard’s Dustin Heise to begin work on creating an Indigenous version of the Long-Term Development framework. Addressing the unique Indigenous pathway was a project that struggled to get activated when Way first presented it to Sport Canada in 2007, and it didn’t become a reality until Sport for Life teamed up with the Indigenous Sport, Physical Activity & Recreation Council (I·SPARC) and Aboriginal Sport Circle.

“Rick Brant was the executive director of I·SPARC, and he funded us to investigate if there really was a need for this, and then Dustin leveraged those funds and had three two-day gatherings with more than 60 Indigenous leaders across the country,” said Way.

“Those leaders agreed that they wanted to create a pathway for Indigenous athletes, and that it should be based on the Long-Term Development framework. So began a journey that took about five years and resulted in the creation of the Indigenous Long-Term Development Pathway (ILTDP).”

Way was thrilled to work alongside Aboriginal Sport Circle board chair Alwyn Morris, a Mohawk and Olympic gold-medallist sprint kayaker who is widely considered to be one of the most influential Indigenous athletes of all time. Their work took place shortly before Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) published its findings on the effects of residential schools in December 2015.

“There was a desire to address the lack of opportunities and infrastructure for Indigenous athletes. The process was very collaborative and interesting, as it was critical for the pathway’s creation that it be led by indigenous leaders and included the teachings of elders,” said Way.

Then the TRC released its report, which called on the government to “take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel.” It was an invigorating moment for Sport for Life, and led to an overwhelmingly positive reception for the new resource. A crucial gap had been filled in their mission to make Long-Term Development accessible to all people living in Canada.

The unchanged mission

Because Sport for Life was initially a contractor-led organization, there was always an incentive for members of the team to bring in new projects. It was a structure that served them well for over a decade, but was becoming harder to manage as the Sport for Life staff continued to grow. Once the staff had expanded to 16 employees, the board knew it was time for restructuring to ensure sustainability and address succession planning, so in 2020 their contractors became full-time employees.

“We haven’t lost sight of the mission while we have rapidly grown to a $5-million organization, which is a validation that the work we are doing is needed and valued. Really, the journey has been mind-blowing,” said Way.

“There’s always criticism when resources or programs are created and then they just sit on the shelf and collect dust. We’re mindful of that, and we’re always trying to figure out how to mobilize knowledge at the local, provincial and national level.”

He believes the key is diversifying the partners Sport for Life works with. With a foundation of $500,000 of core funding from Sport Canada, Sport for Life has been able to expand into other federal and provincial government initiatives, reach foundation funders, engage new sectors and develop its bilingual capacity. By multiplying the sources to leverage its funding tenfold, the Sport for Life team has been able to make the not-for-profit both relevant and sustainable.

Drew Mitchell and Richard Way (centre) accepting award

“We were always responding to requests for proposals in the hopes of getting some extra funds to do the work and expand our expertise. Many, many hours were spent submitting them, some successful and some not. My family was always integrally involved, whether it was my wife Vanessa writing, proofreading, and managing the office, or my children appearing in photo shoots over the years to demonstrate physical literacy,” he said.

In 2017, Sport for Life was given a further morale boost when it was selected by the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) to receive its Award for Excellence in Health Promotion. The CMA Board of Directors recognized “the dedication and efforts of Sport for Life Society toward improving the health of all Canadians through physical activity and sport programming”.

Its portfolio combines contracts with the provincial and federal governments along with funding from self-generated projects. The team has grown to include two dozen employees and over 100 contracted experts. Way’s vision of a staff “that looks like Canada” has begun to come to fruition, with true bilingual capacity and 15 other languages spoken amongst a staff that represents a diverse range of communities and backgrounds.

“Our success has been the result of two decades of hard work. Lots of work. Looking for funds to expand, absorbing overhead costs personally for over a decade. Seeing the potential. But most of all working collaboratively beyond the traditional scope of sport. We are truly a movement that will keep moving, both physically and intellectually, no matter what.”

Click here to see a timeline of the Sport for Life movement.