Dr. Vicki Harber reflects on her multi-decade career in the Canadian sport system

By Will Johnson

Dr. Vicki Harber doesn’t mince words.

The retired Olympic rower and exercise reproductive endocrinologist has been working within the Canadian sport system for much of her career, with a focus on multisport and the female athlete.

For decades she’s been one of the leading voices championing the implementation of the Long-Term Development in Sport and Physical Activity framework within sport organizations, and she’s well-known as the author of The Female Athlete Perspective.

But she didn’t get where she is today by biting her tongue, and she’s not shy about letting people know how she feels the system is currently failing its athletes.

“Right now the system is way too wrapped up in winners and losers, rather than it being about humanity and responsible development. My aspiration was always to try and resurrect what sport did for me as a kid, because it really saved my bacon. Coming from a dysfunctional family, sport provided all of those kinds of things that a traditional family unit is supposed to provide, but for me it didn’t,” Harber told Sport for Life.

“I truly believe that if it weren’t for sports, I would’ve been in jail a couple times over.”

A poster child for multisport

Harber’s interest in exercise first manifested itself while grappling with her three older brothers growing up in Ottawa, all of them athletes and one headed to the Canadian Football League. She was fiercely competitive during activities like potato sack races, and started to develop a passion for using and moving her body. This led her first to join a volleyball team in high school and then a basketball team at university before ultimately finding her sport of rowing while she was working her way through her post-secondary education. It was 1979 when she first took a run at becoming an Olympian.

“I went to a couple of trials and proved myself strong enough to be invited to Olympic selection camp in January of 1980. Having first put my hands on an oar in 1979, people thought I’d lost all my marbles but I worked hard and got named to the 1980 Olympic team within a year,” she said, noting that unfortunately the competition was eventually boycotted by Canada.

Looking back now, she figures she could’ve been the “poster child for multisport”, and indeed she went on to champion it throughout her career. Unfortunately, the large scale culture change needed to support a proper multisport system in Canada never materialized. If anything, she feels like Canada has gone backwards in this regard.

“Though lots of people these days know and understand that multisport is a good thing, our system has completely failed in its infrastructure. Schools are no longer supportive of sport outside their own walls, all kinds of system barriers are making it extraordinarily difficult if not impossible to participate in,” she said.

“It breaks my heart how sport has let down and failed its communities and citizens.”

Dipping her oar in the water

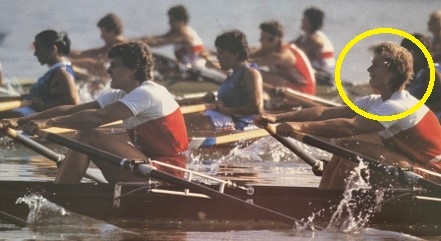

Following the Olympic boycott, Harber became a sessional instructor at McMaster University while continuing her rowing training in St. Catharines. She began her Master of Science (MSc) in 1981, which meant the next three years were a flurry of academics, training, and international competitions. She ultimately competed in the 1984 Olympics, which was the zenith of her athletic life and a hugely life-affirming event.

Harber (right) competing at the Olympics

Pursuing her MSc and PhD while rowing for Canada was an ideal situation for Harber. The focus of her research was exercise reproductive endocrinology – not only did this advance her academic credentials, it fed her craving to understand what was going on for women engaged in high performance sport. She felt there was truth to the cliché that one’s choice of research is called “me-search”, because it’s really a desire to know more about yourself.

“The hardest thing for me has always been recognizing where I might have been of help. My lifelong direction and passion, and I was a high school teacher before I became a university professor, was that a thirst for learning is only as good and as valuable as it is if I can impart that knowledge to others. To get them excited and to have someone else learn and benefit from it,” she said.

She started at the University of Alberta in 1991, continuing to study female athletes, while she gained firsthand experience of developing the talent of young girls when she stepped in as her kids’ soccer coach. During that time she became associated with Steve Norris, an academic working on intentional multisport, a connection that would bring her into the Sport for Life fold in 2005. Her colleague invited her to contribute to the work being done by sport scientists such as Istvan Balyi, Dr. Colin Higgs and Richard Way.

“Steve said I think Canadian Sport for Life would love to get your take on the female athlete, so that was my first toe dip in the water, writing The Female Athlete Perspective. It was kind of like an audition, where they were finding out what kind of person I was so they could decide whether I could be part of their team. And they were thick as thieves,” she said.

They ultimately brought her on, kick-starting a new era of her life. Before long she was working hands-on with national, provincial and local sport organizations while developing learning resources and workshops.

“It was an amazing endeavor while I was still an academic. I loved to learn so that I could impart that knowledge to others, and Sport for Life became that vehicle where I could learn pragmatic, practical things and start interfacing with coaches, boards, administrators, helping them examine how they’re running sport and how they’re looking after athlete development.”

Sport for Canadian women

When The Female Athlete Perspective was first posted to the Sport for Life website in 2008, Harber wasn’t sure what kind of reception it would receive. She feared maybe nobody would read it, or really engage with it. But then the numbers started ticking in, and the emails from sport organizations all over the country wanting to know more. Before she knew it the article had been shared globally and translated into seven languages beyond English and French. She could hardly believe it.

“It was a delight to describe the current understanding of ‘what do we know’ about girls and women in sport and provide some practical recommendations to those working in the space. Making science easy to read and apply became a constant guide for me in all the work I did,” she said.

“This article ignited a multitude of connections with people within the Canadian sport ecosystem (sport clubs, PTSOs, NSOs, and the education and recreation sectors) and set the stage for me to create a workshop for those working with girls and women in sport.”

Harber doing academic work

From there, Harber began getting into the nitty gritty with individual sport organizations. She had a particularly memorable experience while helping Swimming Canada update their Athlete Development Matrix. They had asked for her input on mental and life skills.

“I was blown away by the organization’s willingness to learn and explore new ways of looking at the growth, development, and maturation of the athlete. Swimming Canada thoroughly embraced the foundational importance of executive functions and social and emotional learning skills for athletes as these establish the cornerstone for lifelong health and success, going well beyond performance in sport.”

Harber enjoyed a warm working relationship with Swimming Canada, and was glad to find her thinking aligned with theirs in areas such as LTD implementation, the importance of coaches, and the necessity of strong interpersonal relationships within the swimming community to bring everything to life.

“On top of all this, Swimming Canada shared their resource with other sports wanting to learn more about what they had created. Incredibly generous. Gives me the warm fuzzies just reflecting on this project.”

A system designed for everyone

Over the course of her career, Harber has seen different social trends come and go. But there are some basic ideals that remain constant goals, including gender equity, safe sport, and inclusion. Since her academic focus was on the female athlete, she’s been keenly aware of how the current system fails to live up to some of its loftier standards. In many cases, it’s not because sport organizations don’t have the proper guidance and resources — it’s that they’re failing to use them.

“It’s easy to say we’ve failed at implementation. Implementation of anything, in sport or business or academia, is an underestimated endeavour. The amount of effort over time and tenacity to understand short-term and long-term metrics? It’s layered. And the Canadian system, Sport Canada, Own the Podium, the Coaches Association of Canada, we aren’t good at it,” she said.

“And it’s not because we don’t want to be. I think it’s just a skill set that’s missing from our tool kit.”

And one area where sport organizations need to improve is ensuring that their programming is designed for everyone, not just the high-achieving few.

“The word inclusiveness has become trendy, and some have lost sight of what it means. I think the idea is every child, in every school, should be able to participate in a sport and get a taste of what it’s like at a level that’s right for them. It should be on their diploma, just as important as any math or language arts or science skill.”

Too much policy, not enough action

Harber coaching a kid’s soccer team

Harber is particularly concerned about the state of safe sport in the country, as she feels she’s been hearing all talk and seeing no progress while stories of sexual and physical abuse rock multiple sport worlds. She hasn’t been shy about making her feelings on the topic known.

“I’ve said things around the table that piss people right off, and I acknowledge if my thoughts do irritate people I’d love to hear from them. But as far as the current safe sport policies go, we’ve got too much policy and not enough action. There’s these guidelines and recommendations, but have we really yet made a dent in the way the athlete is cared for and supported?”

Unfortunately, she thinks the answer is no.

“With the increasing number of stories of abuse coming out, most recently with Gymnastics Canada, I sometimes wonder: at the world class level, is there any safe way to do it? It’s a question I ask, and it’s a difficult knot to untangle. It’s like expecting us to learn a new language and we haven’t been properly educated.”

Happy accidents

Now that she’s reached the end of her career, Harber feels like she’s been the beneficiary of a number of happy accidents that led her through a fulfilling and sometimes exhausting career in the sport world. Now that she’s ready to step away, she’s feeling pleased about what she accomplished since getting her PhD back in 1988.

She’s particularly proud of an 8-hour workshop she developed with Canadian Women & Sport, Canadian Tire JumpStart and Respect Group, about keeping girls actively engaged in physical activity longer. That’s just one example of the lasting impact she’s had, and she hopes it will continue to support incremental culture change.

“I feel like it’s quite an achievement, really. I’m happy to have this kind of information getting out more frequently. People certainly weren’t talking about this when I first started out, so it’s nice to see we’re making some sort of progress. How much progress remains to be seen.”

Ultimately, she’s thinking about herself as a little girl, and she wants everyone to be given the multisport opportunities that she was given. That’s what she spent her whole career working towards, as a way of expressing her gratitude.

“I was always a red and white wannabe, so the fact that I got the chance to compete at the Olympic level and have the career I did really does feel like it came from a series of happy accidents. Almost like it was outside of my control. Obviously I worked hard to accomplish what I did, but I try not to forget how much work it takes to create a system where athletes like me can flourish. That’s why I spent my life trying to give back.”