How to achieve truly inclusive quality sport: a conversation with Cherokee Washington

by Chrissy Colizza

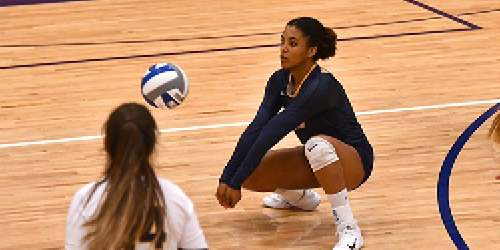

When it comes to delivering true quality sport, collegiate volleyball player and anti-racist educator Cherokee Washington says that before we can move forward, we must continue to acknowledge our faults around inclusivity in sport.

One of the most persistent issues within the Canadian sport and physical activity systems is how members of equity-deserving groups continue to be under-serviced and under-supported. Many sport and physical activity programs have not adequately engaged with these groups to design and deliver quality experiences that meet diverse needs.

One of the most persistent issues within the Canadian sport and physical activity systems is how members of equity-deserving groups continue to be under-serviced and under-supported. Many sport and physical activity programs have not adequately engaged with these groups to design and deliver quality experiences that meet diverse needs.

Sport for Life works with content and context experts to build the detailed components needed for each sport organization to construct appropriate and meaningful Long-Term Development pathways for everyone. This month, Sport for Life caught up with Washington, an inspiring athlete, student, scholar and community leader who has dedicated her educational and personal paths to decolonizing and dismantling systems of oppression through interdisciplinary means and spaces – especially in sport. We sat down with her to talk about her experiences as a cis woman of colour in a mainstream sports pathway and her perspective on what it takes to create and implement truly inclusive quality sport programs.

Sport for Life: Briefly tell us about yourself and your background, specifically in sport.

Washington: In terms of my athletic background, I had the opportunity to play volleyball for Wingate College in North Carolina and Whitman College in Washington state back home in the U.S. as a libero/DS. During my athletic career, I was part of a championship team that went to the Elite 8, I won defensive player of the year my final collegiate season, and was part of another team that won several academic accolades. Although I dabbled in almost every sport – especially track and field – before college, volleyball was where my heart laid in the end. Now, I play beach volleyball whenever I can back home and I hope to play competitively one day.

As a cis woman of colour, I’ve dedicated my educational and personal paths to decolonizing and dismantling systems of oppression through interdisciplinary means and spaces – especially in sport. With an identity at the intersection of womanhood and Blackness, my research specializations and expertise lie in the realms of identity politics, understanding anti-Blackness, anti-racism and anti-colonial education, radical kindness, and compassionate communication. Although my current work and future passions are dedicated to the field of sport sciences, I hold dual Bachelor’s degrees in psychology and honours in rhetoric studies, both of which have allowed me to explore the intersectional nature of sport, politics, and identity.

I’m also a second year Master’s student in McGill University’s Sport Psychology Research Lab. My thesis project currently titled “Black Football Players’ Perspectives on the Effects of Race on the Coach-Athlete Relationship in Canadian Universities” focuses on the ways in which socio-historical contexts and issues of racism within football affect harmony between Black players and their white head coaches. My goal is to not only to give voices to and create space for marginalized folx in sport research, but to subsequently highlight the dire need for cultural competency work in coaching education. I also serve as a student member on McGill’s Kinesiology department and faculty of education Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility committees through which I’ve assisted in EDI related initiatives to better support our underrepresented students and educate the McGill community on issues of identity politics.

On a personal note, I hail from Los Angeles – a city that has a deep history with protest, activism, and politics. With my cultural background, my various communities that have taught me to radically learn and critically think, my role as an abolitionist, my life experiences, and my hometown roots, I consider myself highly lucky to be engaged in this work.

Sport for Life: Tell us about your involvement as an anti-racist educator and why coaches and sport organization stakeholders need to get educated in this domain.

Washington: I’ve always been involved in EDI and anti-racism work for as long as I can remember, especially growing up in the era of Black Lives Matter and other social movements. In short, I attended an anti-racism conference in high school that opened my eyes to an entire toolkit of strategies for combating discmrination which I was missing as a young person of colour navigating the world. It was through this conference that I discovered concepts like critical race studies, the “isms,” and much more – all answers I’d been seeking in order to make sense of my experiences in predominantly white institutions (PWI) and other spaces I was in.

My newfound knowledge led me to study rhetoric in college which provided me with a background in identity politics and developed my interest in EDI related topics. Outside of academic settings, I’ve been blessed to be a member of radical learning communities such as Noname’s Book Club and The Teach Out that are devoted to critically investigating and creating a world of liberation through an abolitionist lens. Without these communities, I wouldn’t be the activist researcher I am today.

Along with my academic background, during the third year of my volleyball career, I chose to kneel in support of Colin Kaepernick at all of our home games which resulted in my receiving anti-Black behavior from my head coach. This experience in particular was the wake up call I needed to really understand how my activist, racial, and athlete identities were always meant to intertwine. My Master’s thesis project is an indirect study on the ways my own college coach treated me and how race caused disharmony in our relationship during a socio-politically tumultuous time in the U.S. In sum, I always knew I wanted to use this expertise in a sports setting and the universe brought me to McGill in a strangely cathartic way.

As for why coaches, stakeholders, and educators in sport domains need to educate themselves on anti-racism, it’s simple: it’s time. Coaches are typically only required to undergo sexual misconduct training while microagggression training isn’t ever considered as an important piece of a coach’s (or human being’s) education. Many sport entities often get away with committing microaggressions towards players without penalties or even a slap on the wrist, which leaves athletes left to deal with the emotional and mental repercussions alone. We don’t take microaggressive behavior nearly as seriously as we should in sport and thus, education is necessary.

On a similar note, sport research and coach training often carters to the dominant group of white, able-bodied, cis, heterosexual, men while all other individuals with non-dominant intersecting identities are considered as “others.” In other words, we only care about and focus on white men in research, workshops, etc and don’t even think about other groups and their culturally specific needs. Sport entities can’t shy away from these truths anymore, especially today. It’s important to educate folx in all domains on the ways in which identity politics have affected their field and sport is no exception. Even at the beginning of its conception, sport has been racialized and gendered to keep certain groups out.

Whether it be Bill Russell, Billie Jean King, or Naomi Osaka, sport, race, politics, and identity go hand in hand as much as certain stakeholders don’t want them to. Especially in the U.S., not many folx know that sport organizations such as the NBA were built from the labour of Black players who have been historically exploited despite the racial demographics in the league today. Few coaches know and some choose to ignore the not so cute histories of our beloved sport organizations (the NFL being one of the worst cases). It’s time for coaches and other entities to be honest and look at the damage they’ve done to the athletes they’re meant to support.

Sport for Life: Why is it important to create and implement inclusive sport programs? What does such a program look like to you?

Washington: Although we often believe that sport is an inclusive space, this is unfortunately not usually the case. With the new anti-trans laws, policy changes that bar certain groups from participating in sport, and many more barriers, it’s important to ensure sport environments are inclusive so that everyone can utilize their right to partake in athletic activities. In implementing these types of programs, we can offer safety, support, and acceptance of any individual who chooses to play sport regardless of their background. Our identities are intersectional and unique – they should be treated in a way that’s not exclusionary, but just the opposite.

I’m not exactly sure what this kind of programming looks like yet. I do know it must include education of foundational concepts, interdisciplinary, active implementation of strategies and tools, open minds, open hearts, and the willingness to get uncomfortable.

I hope to create this type of programming in the future.

Sport for Life: What are your main goals for the work you are doing? What do you hope to achieve?

Washington: Ultimately, I want to make sure that athletes of marginalized backgrounds, especially athletes of colour, are properly supported in the way they should be. Similarly, I hope to shed a bright spotlight on the injustices, issues, and straight up discrimination that happens every day in sport by offering coaches and other entities ways to combat and avoid them. We’re in the middle of a new iteration of the civil rights era and we as individuals have to choose how we want to contribute to the movements that we’re seeing today. I hope to challenge oppressive, colonial, antiquated systems that no longer serve us and ultimately decolonize the current practices that we use in sport scholarship through education and other strategies.

In other words, I often ask myself in an abolitionist world, what would sport look like? How can we create the most inclusive, accepting, accessible, and diverse version of sport possible in the future? How can we critically engage in the historical issues that we still see in sport today? It’s time we all learn together and make sport a more equitable domain by answering these types of questions.

Sport for Life: What changes do we have to make to adapt mainstream pathways for sport development to provide more inclusive sport pathways?

Washington: There are so many things we need to change structurally, policy-wise, etc. in sport development, the list is too long to share here. However, I’ll offer one simple step. We have to admit there’s an inclusivity problem that’s been present in sport from the beginning. We can’t move forward and become more inclusive if we don’t admit there’s a problem in the first place. It’s time for us to tell the truth and admit our faults.

Resources:

- Long Term Development in Sport and Physical Activity

- Noname’s Book Club

- The Teach Out

- https://www.blacklivesmatter.ca/